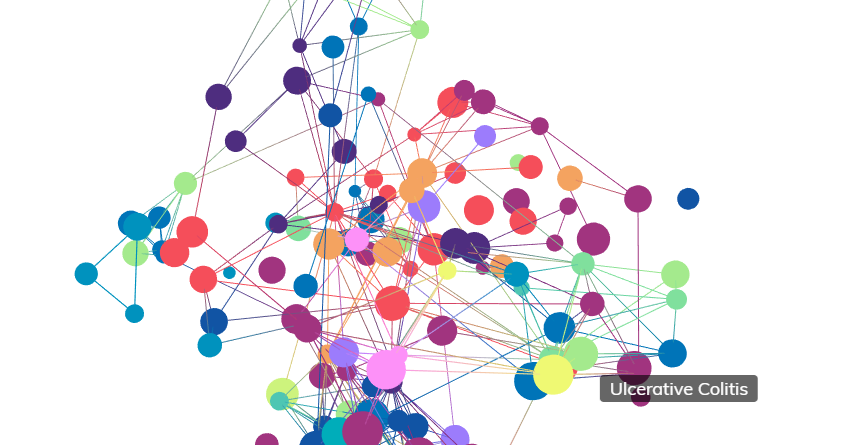

Ulcerative Colitis

- Non-communicable

- Autoimmune

- Gastrointestinal

Ulcerative colitis (UC) falls under the category of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), together with Crohn’s disease (CD). It is an idiopathic and autoimmune-mediated inflammation of the epithelial mucosa of the rectum and/or colon, which leads to a range of intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms. Although not fully elucidated, its aetiology is thought to be multifactorial in origin, with both genetic predisposition and environmental factors playing a role in pathogenesis. UC is associated with a wide range of inflammatory conditions, including hepatic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular comorbidities, and it is noticeably linked to mood disorders and anxiety. Management follows a step-up approach and aims to induce clinical remission and improve quality of life.

Clinical Features

UC may present with both intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms. The most common presentation of UC is watery diarrhoea with blood and/or mucus. Abdominal bloating and discomfort are also commonly reported. Extra intestinal manifestations of UC may include nail clubbing, aphthous oral ulcers, erythema nodosum, pyoderma ganrenosum, conjunctivitis, episcleritis and iritis. Furthermore, it may also lead to large joint arthritis and sacroilitis. As a result of the increased bowel movements and possible malabsorption, patients may present with systemic symptoms, such as general

malaise

Malaise

General feeling of discomfort or unease, usually an early indicator for other symptoms to follow.

, lethargy, anorexia and weight loss.

The severity of UC is determined by both clinical signs and symptoms, including frequency of watery diarrhoea per day, rectal bleeding, resting pulse rate, temperature, as well as serological tests, such as haemoglobin levels and erythropoietin sedimentation rate (ESR). UC is considered mild if less than 4 liquid bowel movements a day are experienced; moderate if that increases to 5; and severe if more than 6 daily episodes are reported. In acute attacks, patients might pass up to 10-12 liquid stool a day.

Complications

A serious complication of acute UC is toxic megacolon which has high risk of bowel perforation, whose consequences can be life-threatening. Toxic megacolon is diagnosed with a plain abdominal x-ray which shows a colonic dilatation of more than 6 cm. Other complications of acute attacks are hypokalaemia and venous thromboembolism. Chronically, UC is linked with increased risk to develop colorectal carcinoma, as a result of the metaplastic changes in the colonic histology. Patients are therefore advised to attend regular endoscopic monitoring to exclude any neoplastic transformation in the colonic epithelium.

Examination and investigations

According to the severity of the disease, patients might present with tachycardia, temperature and general

malaise

Malaise

General feeling of discomfort or unease, usually an early indicator for other symptoms to follow.

. An abdominal examination may reveal some tenderness to palpation in the lower abdomen, and generalised distention. A digital rectal examination often shows a normal anus, yet may reveal the presence of blood.

Because of the unspecific signs and symptoms, investigations are essential for the diagnosis of UC, and include:

- Blood tests: full blood count commonly shows increased white cell and platelet count, with or without iron deficiency anaemia. The inflammatory markers C- reactive

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication. (CRP) and ESR are often raised. Patients are also likely to be p-ANCA (Perinuclear Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies)- positive. - Stool tests: in order to rule out any infective cause of diarrhoea, stool should be tested for Clostridium difficile toxin, as well as other microbial toxins if there is any relevant travel history. Faecal calprotectin is an unspecific inflammatory marker, which is normally raised in UC.

- Colonoscopy: Colonoscopy with mucosal biopsy is the gold standard investigation for UC diagnosis. Nevertheless, in acute and severe UC attacks full colonoscopy must be avoided due to the risk of bowel perforation.

- Imaging: An abdominal ultrasound is a non-invasive test that may reveal free fluid and air in the abdominal cavity. Nevertheless, it does not show the degree of inflammation, hence a colonoscopy is preferred.

In acute attacks, a plain abdominal X-ray must be urgently performed to exclude toxic megacolon.

Pathogenesis

The

pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The biological mechanism that leads to a state of disease. It can refer to the origin and development of a disease, as well as whether it is recurrent, chronic and acute.

of UC is complex and multifactorial in origin, with some aspects still not being completely elucidated. Genetic predisposition and positive family history increase the likelihood of developing UC. In addition, several environmental factors predispose to disease onset, including high fat and high-carbohydrate diets, overuse of antibiotics, lack of breastfeeding, and use of oestrogen therapy; whilst smoking appears to be protective.

In ulcerative colitis, environmental triggers together with genetic predisposition cause dysregulation of the intestinal immune system and imbalance in the gut microbiota. Collectively, these are the major contributors in UC aetiology, driving an autoimmune response which ultimately leads to long-standing inflammation of the colonic epithelium. Differently from Crohn’s Disease where the entire digestive tract is involved, in UC the inflammatory process occurs in the colon only. The inflammation may be limited to the rectum (known as proctitis), or involve part of or the entire colon (known as colitis).

Intestinal immune system

The immune system of the intestines consists of two main components: the epithelial layer – which is made of mucus-producing cells (including the Goblet cells), acting as a protective barrier against microbes - and the cells of both the innate (e.g. dendritic cells) and the acquired (e.g. lymphocytes) immune system. In UC, the structure of the mucus layer is altered, possibly due to misfolding of structural proteins. In active disease, the immune response is also upregulated, with the immune cells and cytokines infiltrating in the faulty epithelial structure, and damaging the colon.

Both innate and adaptive immunity are implicated in disease

pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The biological mechanism that leads to a state of disease. It can refer to the origin and development of a disease, as well as whether it is recurrent, chronic and acute.

, originating a complex cascade of reactions and interactions between immune mediators and cytokines. Ongoing and active inflammation sees an increased expression of toll-like receptors 2 and 4, and consequently of neutrophils and dendritic cells. Lymphocytes are also major contributors of the active inflammatory process, with the major drivers being IgG-producing B cells and cytotoxic T cells stimulated by cytokines (especially interleukin-5, -13 and -17). On the other hand, major players of chronic inflammation are innate lymphoid cells.

Dysbiosis

Still unclear if cause or effect of the mucosal inflammation, imbalanced colonic flora (or dysbiosis) is commonly seen in individuals with UC. The alteration in microbial biodiversity includes an increase in Gammaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae, and a decrease in Firmicutes.

Comorbidities

Individuals suffering from IBD (both UC and Crohn disease) are at higher risk to develop secondary healthy problems (known as comoribities) which should be differentiated from the extra-intestinal manifestations of the disease discussed in the Clinical Features section. In IBD, hepatic, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, psychiatry and musculoskeletal comorbidities are commonly seen.

Hepatic comorbidity: Deranged liver function tests are commonly reported in chronic inflammation of the the bowel. In addition, there is a potential association between IBD and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a severe inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts.

- Gastrointestinal comorbidity: Individuals with IBD are more prone to Helicobacter pylori infections, a common cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers, and to develop celiac disease and gluten-sensitive enteropathy.

- Cardiovascular comorbidity: IBD increases the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), as risk factor for both venous and arterial thrombotic events, and atherosclerosis.

- Psychiatric comorbidity: Possibly a consequence of the impact of the disease on quality of life, there is a high prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders in patients affected by IBD.

- Musculoskeletal comorbidity: Although joint pain and swelling might present as extra-intestinal manifestations, UC may also occur in conjunction with enteropathic arthorpathy, a seronegative form of arthritis.

Cellular Characteristics

Microscopically, active UC exhibits features of ongoing inflammation and disruption in the architecture of the colonic mucosa. These changes are limited to the colon, and continuous throughout its mucosal layer. These two features allow to differentially diagnose UC from CD, where the inflammation extends beyond the colon and exhibits a “skip lesion” pattern.

In UC, the neutrophil-mediated inflammation progressively leads to epithelial injury, hence distortion of the colonic crypts. Histologically, this may present as crypt shortening, crypt abscess, immune cell infiltrate (known as plasmacytosis), eosinophils recruitment, and lymphocyte aggregates in the lamina propria. Indeed, healthy colonic crypts are uniformly spaced and in contact with the muscularis mucosae underneath, whilst in UC they become shortened and branched, and lose contact with the structure underneath, leading to erosions and cellular infiltrate. The distorted crypt architecture correlates with the clinical features of bleeding and loose stools. Another important microscopic change of UC is Paneth cell metaplasia, which defines the presence of Paneth cells in the left colonic epithelium. These cells, normally found in the right colon only, are hallmark of chronicity.

The diagnosis of UC is through histological evaluation of the colonic mucosal layer. For a reliable diagnosis, current clinical evidence recommends at least two biopsies to be taken endoscopically from six areas of the intestines (terminal ileum, ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colon, as well as the rectum), regardless of the macroscopic appearance of the tissue.

On endoscopy, it is also paramount to exclude neoplastic changes and polyps. Due to the increased risk to develop colorectal carcinoma, individuals with UC should undergo surveillance endoscopy on a regular basis.

Genetics

As briefly discussed in the

pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The biological mechanism that leads to a state of disease. It can refer to the origin and development of a disease, as well as whether it is recurrent, chronic and acute.

, positive family history (especially first degree relatives) of IBD, in particular UC, predisposes to disease onset. Indeed, twin studies have shown higher concordance rates in monozygotic twins, compared to dizygotic. Nonetheless, UC is a polymorphic disease, with multiple genes being involved in pathogenesis.

genome

Genome

A collection of DNA which is capable of developing and maintaining an entire organism.

-wise association study (GWAS) identified up to 200 loci to be somehow associated with the

pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The biological mechanism that leads to a state of disease. It can refer to the origin and development of a disease, as well as whether it is recurrent, chronic and acute.

of IBD, with the majority of them shared by both UC and Crohn disease.

The TNFSF15 locus – encoding a

cytokine

Cytokine

A broad category of small proteins released by a range of cells (including immune cells like macrophages, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes) that act through receptors and are important for a range of processes including cell signaling, inhibition, maturation and proliferation.

from the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) family, has been linked with increased risk for IBD. Other loci possibly associated with UC predisposition are HNF4A and CDH1, both encoding for proteins associated with barrier functions. Some other studies linked loci encoding for interleukins, such as IL12B, with increased disease susceptibility. Dysregulation of the genes STAT3 and JAK2, both responsible for the signal transduction in

cytokine

Cytokine

A broad category of small proteins released by a range of cells (including immune cells like macrophages, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes) that act through receptors and are important for a range of processes including cell signaling, inhibition, maturation and proliferation.

pathways, is also thought to exacerbate the disease.

Treatment

Given the relapsing and remitting pattern of UC, the aim of treatment is induction and maintenance of remission, with consequently symptom relief, improvement in quality of life, and endoscopic healing. Nonetheless, histological findings tend to poorly correlate with clinical evaluation and patient’s presenting complaints.Management of UC follows a step-up approach based on disease severity and inflammation extent, as proven endoscopically.

Mild to moderate UC

Aminosalicylates (5-ASA) are the first line therapy for mild-moderate disease. 5-ASA exhibit anti-inflammatory properties through a wide range of mechanisms, including interference with prostaglandin and leukotriene production, inhibition of leukocyte function and

cytokine

Cytokine

A broad category of small proteins released by a range of cells (including immune cells like macrophages, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes) that act through receptors and are important for a range of processes including cell signaling, inhibition, maturation and proliferation.

synthesis, as well as scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

According to the extension and degree of the inflammation, 5-ASA can be administered topically (e.g. in form of suppositories in proctitis), or orally (e.g. in form of tablets in extensive disease). The starting dose is usually 2.0-2.4 g a day, and can be increased up to 4.8g. On average, patients experience improvement in their symptoms within 14 days, though it might take up to 8 weeks for clinical remission of the disease. Once on remission, 5-ASA are typically continued at the same or lower dose – basing on clinical judgment - for maintenance. Sulfasalazine, which is metabolised into 5-ASA, is equally efficacious, though less commonly prescribed as not well tolerated.

If not achieved with aminosalicylates, remission is induced with corticosteroids via either suppository in case of proctitis, or oral tablets in case of extensive colitis. If systemic steroids are needed, either oral steroids with “minimal systemic activity” (such as budesonide-multimatrix and beclomethansone dipropionate), or glucocorticoids (such as prednisolone) may be chosen. In either case, steroids should be continued for two weeks, and then tapered down by 5-10mg a week. It is important to highlight that corticosteroids are only used to induce remission, and for a limited time (e.g. weeks), and they are not administrated for maintenance. Once off steroids, remission is usually maintained with 5-ASA.

If patients require two or more cycles of steroid therapy a year, and/or have poor prognostic factors (e.g. extensive disease, ulcerations and young age at onset), they should be treated for moderate-severe UC.

Moderate-severe UC

Moderate-severe disease is managed with thiopurines (such as azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) or biological agents, or a combination of both. Efficient in both induction and maintenance of remission, biologics used in UC are predominantly anti-TNF alpha drugs, and include infliximab, adelinumab and golinumab.

Acute severe UC

Acute severe disease is defined as at least six bowel moments with bloody diarrhoea a day, and one of the following signs of acute illness:

- Heart rate > 90 beats per minute

- Temperature > 37.8 degrees

- Haemoglobin count < 10.5 g/dl

- ESR > 30 mm/H

In case of acute presentation, patients should be admitted and started on intravenous corticosteroids. If no response is seen within 3-5 days, medical rescue therapy with ciclosporin or infliximab should be commenced. The last resource in case of lack of response with pharmacotherapy is surgical colectomy.

Surgery

Surgery is performed in case of haemorrhage, perforation, dysplastic findings not suitable for endoscopic resection, or colorectal carcinoma. On those instances, restorative proctocolectomy with ilieal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPPA) is the operation of choice. As outlined above, in acute and severe UC refractive to medical therapy a subtotal colectomy is usually indicated.

Epidemiology

UC is a disease mainly seen in industrialised countries. Northern Europe has the highest incidence, followed by Canada and Australia; though disease incidence has been increasing in Asia as well. Similarly, the prevalence of UC is the highest in Europe, Canada and USA.There is no gender predominance, with males and females being equally affected by the disease. Age wise, UC is distributed bimodally, displaying a first peak in the 2nd and 3rd decade of life, and a second peak between the 5th and 8th.

There are no conclusive studies on race or ethnicity predisposition. Nonetheless, it has been observed that the Jewish population has a 3 fold increased risk to develop IBD, compared to non-Jewish.

References

- "Kumar, P. and Clark, M.; Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine. Ninth Edition (2017); pages 404-415"

- "Wilkinson, I.B.; Raine, T.; Wiles, K.; Goodhart, A.; Hall, C.; O’Neill, H. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Tenth edition (2017); pages 262-263."

- "Annahazi, A.; Molnar, T.; Pathogenesis of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Similarities, Differences and a Lot of Things We Do Not Know Yet (2014); Journal of Clinical and Cellular Immunology, 5(253). doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000253"

- "Hibi, T; Pathogenesis and Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis (2003); The Journal of Japan Medical Association, Volume 46, No.6, pages 257-262 "

- "Ungaro, R.; Mehandru, S.; Allen, B.P.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Colombel, J.; Ulcerative Colitis (2017), The Lancet, Volume 389, Issue 10080, pages 1756-1770"

- "Lopez San Roman, A.; Munoz, F.; Comorbidity in inflammatory bowel disease (2011), World Journal of Gastroenterology, Volume 17(22), pages 2723-2733"

- "Gajendran, M.; Loganathan, P.; Jimenez, G.; Catinella, A.; Ng, N.; Umapathy, C.; Ziade, N.; Hashash, J.G.; A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis (2019), Disease a month, available online only "

- "Punchard, N.A.; Greenfield, S.M.; Thompson, R.P.H; Mechanism of action of 5-aminosalicylic acid (1992), Mediators of inflammation, Volume 1(3), pages 151-165"

- "Nguyen, N.H.; Fumery, M.; Dulai, P.S.; Prokop, L.J.; Sandbron, W.J.; Hassad Murad, H. et al, Comparative Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological agents for management of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis, The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Volume 3(11), pages 742-753"

- "Adams, SM.; Bornemann, P.H.; Ulcerative Colitis (2013), American Family Physician, Issue 87(10), pages 699-705"