Breast Cancer

- Non-communicable

- Cancer

- Carcinoma

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) cancer is “a generic term for a large group of diseases characterised by the growth of abnormal cells beyond their usual boundaries that can then invade adjoining parts of the body and/or spread to other organs”. There are more than 200 types of cancers that can occur in any part of the human body. It is a genetic disease, which means that it is caused by alterations in the cells’ DNA, especially in genes that control cellular growth and division. Breast cancer (BC) is the neoplasm that has in the breast its primary site of growth. It is the most common type of cancer in women, excluding non-melanoma skin neoplasms, contributing to approximately 2.4 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2015. BC is the fifth most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths overall, causing more than half a million deaths worldwide in 2015. BC is also the most common cause of cancer deaths in women between 20 and 59 years of age.

Clinical Features

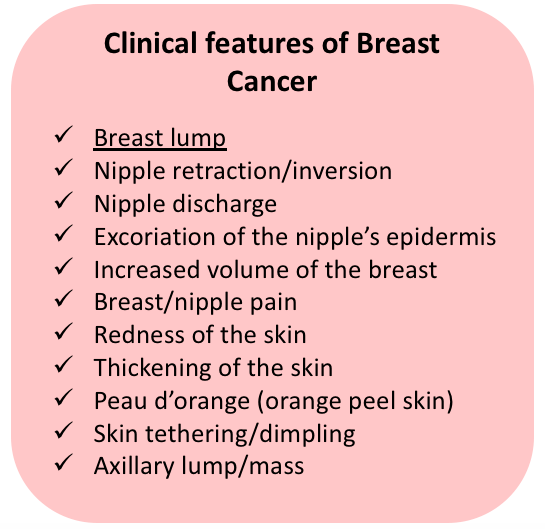

BC presents itself with a lump in around 70% of cases, identified either through palpation or imaging tests (mammography and/or ultrasound). The majority of palpable nodules are discovered by patients during self-examination. Most breast lumps, however, are benign (non-cancerous).

Many other signs can be found in cases of BC, as listed in the figure below. These, however, are less frequent and frequently a sign of more advanced disease.

Figure 1. Clinical features of Breast Cancer.

The inflammatory carcinoma is a special presentation of BC, which combines peau d’orange (oedema of the skin producing the dimpled texture of an orange peel) with warmth, swelling and tenderness of breast. These alterations are caused by the obstruction of the dermal lymphatics with carcinogenic emboli. The inflammatory carcinoma can be mistaken for acute mastitis, due to the very similar presentation.

Paget’s disease is another special presentation of BC. It is caused by the presence of an intraductal carcinoma (DCis) reaching the epidermal layer of the nipple’s skin, producing a dermatitis that can be erroneously diagnosed as an eczematoid affliction. The alterations begin in the nipple but can extend to the skin of the areola. Despite being mainly characterised by the presence of an extensive DCis, an invasive component may also be found in some cases.

Screening & Diagnosis

Screening of BC has the objective of identifying the disease in an early and clinically unapparent stage. The idea is that an early diagnosis allows treatment to be less aggressive and with higher survival rates.

The diagnosis of BC is done by the combination of clinical history, clinical breast examination, imaging techniques and histopathological assessment.

Mammography

Mammography is the primary method for early diagnosis of BC, shown to reduce BC mortality by approximately 20% when implemented in population-based screening programmes. As a screening modality, it is applied in order to identify small, nonpalpable abnormalities. It can also be used to further evaluate alterations found on the screening mammography, through magnified images and selective compression, as well as to guide diagnostic procedures such as biopsies. The method’s sensitivity is highly dependent on the density of the breast – in women younger than 30 years of age the mammogram usually lacks definition, due to the higher density of the breast. With the aging process, the breast tissue is progressively substituted by adipose tissue, which is radiotransparent, allowing contrast with possible lesions. Still, it is estimated that up to 15% of all clinically evident BCs show no abnormality on the mammographic images.

According to the recommendations of the American Cancer Society, mammographic screening should be performed annually in all women from 40 years of age onwards, as long as the woman presents good health. Clinical breast examination is recommended annually, in association to the mammogram.

Ultrasonography

The ultrasonography of the breast is not a recommended modality for BC screening, mainly due to the fact that it is an operator-dependent method. On the other hand, the ultrasound is a very important complementary method to the mammography. It is convenient in differentiating between solid and cystic lesions, which can be very similar on a mammogram. It is also useful to guide the biopsy of ultrassonographically evident abnormalities. Other indications for ultrasound are palpable alterations (specially in younger patients and pregnant women), mammographic alterations such as architectural distortions, and suspicion of axillary lymph node metastasis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Although not routinely recommended as a screening tool, MRI has been progressively applied in the assessment of breast alterations. MRI for BC screening is recommended by the American Cancer Society for women with increased (>20-25%) lifetime risk of BC – BRCA mutation carriers or patients diagnosed with other genetic syndromes with higher risk for BC, patients with strong family history, patients who received radiation to the chest between 10 to 30 years of age.

As a diagnostic modality, MRI is useful in evaluating patients with breast implants (due to the limitations of the mammogram on these cases), defining the extent of the breast

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

especially when there is a suspicion of chest wall involvement, and complementing mammography and ultrasonography when findings are uncertain.

The high sensitivity (>90%) of the breast MRI added to its moderate specificity, however, make the method more prone to false-positive results, leading to additional imaging studies and biopsies.

Breast Biopsy

For nonpalpable lesions, image-guided biopsies are necessary. When a lump is present, an ultrasound can be used; when only microcalcifications or architectural distortions are being investigated, the specimen is collected through stereotaxic procedure. Both the fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and the core-needle biopsy can be used, however the core-needle involves the recovery of a larger specimen which allows the pathologist to analyse the tissue’s architecture and determine if invasive cancer is present. In contrast, the FNA produces a sample of loose cells that can only be evaluated cytologically, making the differentiation between carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma not possible. Palpable lesions can be approached both with FNA and core-needle biopsy, using a free-hand technique.

It is important to note that, despite the low rate of false-negative presented by core-needle biopsies, negative results should not mean the end of the investigation when there is suspicion for malignancy. New biopsies, preferably guided by imaging methods, should be considered.

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS®)

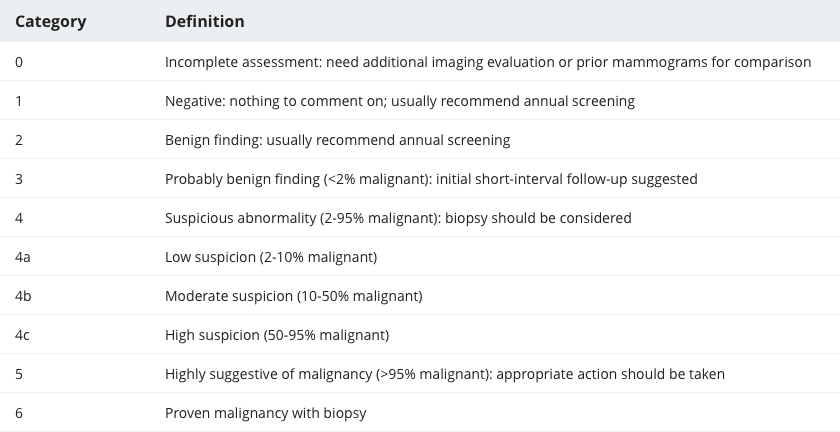

The BIRADS® was first created in 2003 by the American College of Radiology, with the objective of categorising the degree of suspicion for malignancy of findings from mammograms, breast ultrasounds and breast MRI. The system allows the communication of the findings in a standardised manner that can be understood by multiple professionals in different settings.

The BIRADS® categories, with their respective definitions, can be found below.

Table 1. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS®) classification for Mammography, Breast Ultrasound and Breast MRI (adapted from the American College of Radiology's BI-RADS® Atlas)

Pathogenesis

Although the exact carcinogenic process is yet to be determined, it is known that BC is a product of a sequence of epithelial changes in the terminal ductolobular unit. These changes are caused by several mutations in the cells’

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA)

The nucleic acid molecule that contains all the genetic information regarding the development and functioning of all living organisms is known as deoxyribonucleic acid.

, affecting genes responsible for managing cellular proliferation, growth and apoptosis. Considering that BC is a multifactorial disease, these genetic mutations seem to be triggered by a combination of elements.

Atypical hyperplasias have the potential to progress into carcinoma in situ, which can then progress to invasive carcinoma. This progression is not linear, and regression is possible. In the majority of cases, however, carcinoma in situ will lead to invasive carcinoma. The link between typical hyperplasias and atypical hyperplasias is still unclear, mainly because mammary cells are physiologically capable of producing hyperplasia under several stimuli (for lactation, for example).

Once a carcinoma in situ is present, the natural history of the disease tends to progress to invasive cancer restricted to the breast, extension to adjacent structures, spread to regional lymph nodes, and dissemination to distant organs.

Comorbidities

In cases of hereditary BC, an association with other malignant diseases can be found. In carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, there is a strong association between breast and ovarian cancers; pancreatic and colon cancers have also been reported. Mutations in genes such as CHEK2, PALB2 and PTEN are linked to a higher risk for BC and others cancers including colorectal, gastric, prostate, thyroid, pancreatic and endometrial. Mutations in the TP53 gene are associated to a greater risk for BC and for several other malignancies such as sarcomas, bone cancers and central nervous system (CNS)

tumours,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

typically at a young age.

Cellular Characteristics

Carcinoma in situ

The Carcinoma in situ is defined as a non-invasive neoplasm, and is split into two types, Lobular Carcinoma in situ (LCis) and Ductal Carcinoma in situ (DCis). Although believed to be a malignant entity in itself in the past, the LCis is now considered a risk factor for invasive BC. In contrast, the DCis is proven to have the potential to become invasive.

To define if the cancer is in situ or invasive, it is imperative to determine whether the cancer cells invade through the basement membrane of the mammary ducts or not. When the cells are confined within the ductal and alveolar limits without invading the basement membrane and reaching the stroma, then the carcinoma is classified as in situ.

Lobular Carcinoma in situ

LCis develops in the terminal duct lobular units and presents itself with large cells that distend and distort these lobular structures. Cytoplasmic mucoid globules are very characteristic in this affliction.

LCis is usually an incidental finding from breast biopsies, therefore its frequency in the general population is unknown. LCis can present microcalcifications that are identified in mammograms.

Despite the fact that women with LCis develop invasive BC in around 30% of cases, LCIS is considered a marker of higher risk for BC and not a direct precursor. In women with a previously diagnosed LCis, around 65% of the subsequent invasive cancers are ductal. Bilateral foci of LCis are found in 50% to 70% of cases.

Ductal Carcinoma in situ

Also known as intraductal carcinoma, the DCis is recognised by the proliferation of malignant epithelial cells within the intact basement membrane of the mammary ducts. Women diagnosed with DCis have higher risk of developing invasive BC, corresponding to five times the risk of the general population. The invasive cancer develops in the same breast that contained the DCis, corroborating with the theory that DCis is a direct precursor of invasive BC.

As opposed to what is reported for the LCis, the DCis is predominantly unilateral, and occurs bilaterally in only 10% to 20% of cases.

DCis presents a very good long-term prognosis, with 10-year survival rates superior to 95%.

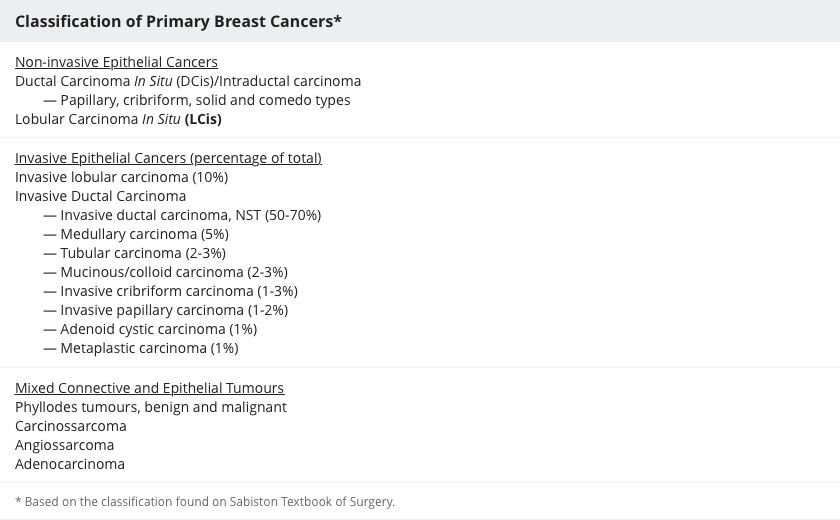

Invasive Breast Carcinoma

Invasive cancers are characterised by the absence of overall architecture as well as an infiltration of the connective tissue of the breast by malignant cells. Invasive carcinomas are broadly divided into lobular and ductal types. Invasive ductal cancer is the most common type, responsible for roughly 70% of infiltrating BCs. In contrast, invasive lobular carcinoma is diagnosed in only 10% of the cases of BC. Mixed variations between ductal and lobular carcinomas are also described.

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

This category of invasive BC includes different types, namely invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type (NST), medullary carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, papillary carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, invasive cribriform carcinoma, invasive papillary carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma and other rare types.

Invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type (NST) is found in around 70% of all BC cases. It typically occurs in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women. It produces a single, cohesive mass, where the malignant cells are found in small clusters. Positive expression of oestrogen receptors (ER) is found in the majority of cases. Axillary lymph node metastases are found in up to 60% of cases.

Medullary carcinoma is frequently present in BRCA1-associated BCs. Mucinous carcinoma (colloid carcinoma) and papillary carcinoma are more common in the elderly. Tubular carcinoma usually occurs in women in the perimenopausal phase.

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

The invasive lobular cancer accounts for around 10% of all BC cases. Its invasion occurs in a single file fashion, not forming a defined mass, allowing the cancer to remain clinically and mammographically occult for a long time. The invasive lobular carcinoma is frequently bilateral and expresses oestrogen receptors in up to 90% of the cases. Due to its insidious growth, it is diagnosed in more advanced stages, when compared to the invasive ductal carcinomas.

Table 2. Classification of Primary Breast Cancers (adapted from Sabiston Textbook of Surgery).

Molecular Markers

Despite the similarities in the histological characteristics, breast

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

can present various molecular characteristics that are coded by their own genetic material. Some of these molecular characteristics are relevant as prognosis predictors and can guide the choice of specific treatments.

A good example of this is the hormonal receptor. BCs can express oestrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PR, respectively) in different levels.

Tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

that have a higher expression of ER/PR are known as hormone-dependent and are usually sensitive to endocrine therapy. Around 70% of all BCs are ER-positive, and between 60 and 65% are PR-positive.

Another important molecular marker is the HER-2

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

, also known as c-Erb-B2/neu

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

. This

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

has its expression amplified in roughly 20% of BCs. Its clinical relevance is due to the fact that

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

said HER2-positive tend to be more aggressive and grow faster. This

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

, however, can be targeted by anti-HER2 drugs (trastuzumab and pertuzumab), which have shown to inhibit the growth of HER2-positive

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

both in laboratory models and in clinical trials. Amplification of HER2 is found in 10 to 35% of invasive BCs.

Cancers that do not express neither ER/PR nor HER2 are called triple-negative. These

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

tend to have a poorer prognosis due to the absence of targeted therapies.

Breast

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

rare routinely tested for the expression of ER, PR and HER2 by a technique called Immunohistochemistry. The immunohistochemistry uses antibodies directed to the different receptors, to identify the presence and the quantity of those receptors.

Staging

After a patient has been diagnosed with BC, the cancer staging is performed. Cancer staging is the categorisation of the disease based on the quantity of cancer in the body and where it is located. It describes the extension of the disease, in terms of the size of the primary

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

and its eventual extension to other organs.

Staging helps in the planning of the therapeutical management of the patients and allows for a better understanding of prognosis in different cases.

The determination of the stage of the disease is done before any kind of treatment is performed, based on physical examination and imaging studies (clinical staging) and on definitive surgical treatment by pathologic examination (pathologic staging).

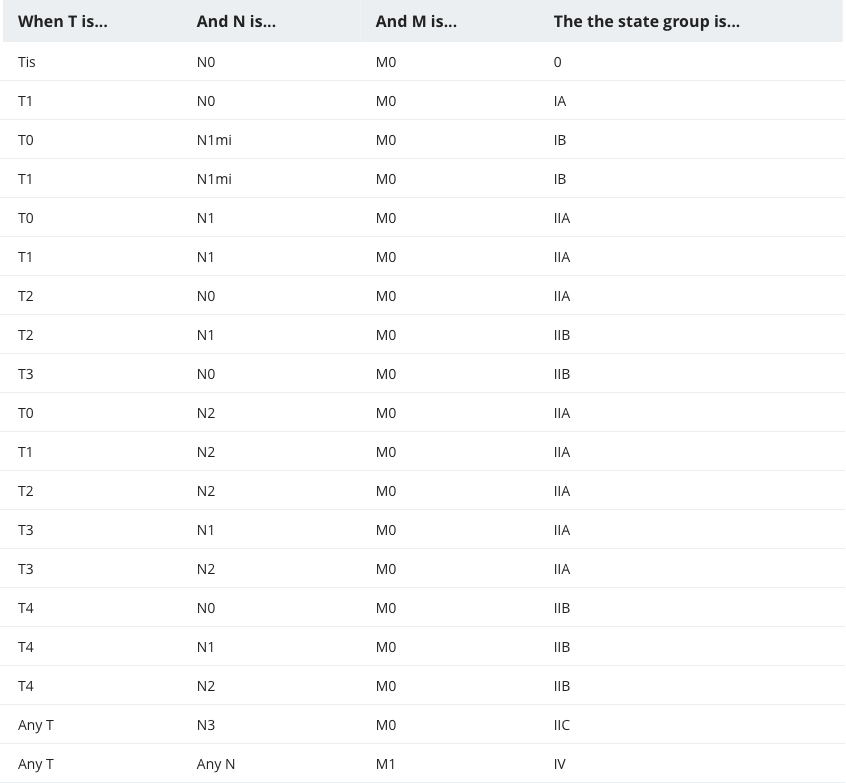

The TNM Staging System is the most commonly used classification for BC. It was developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and uses 3 aspects of the disease: the extent of the primary

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

(T), the extent of the lymph node involvement (N), and the presence of distant metastasis (M). Based on the different combinations of the T, the N and the M, an overall stage of 0, I, II, III, IV is attributed, which correspond risk categories that define prognosis and direct treatment recommendations.

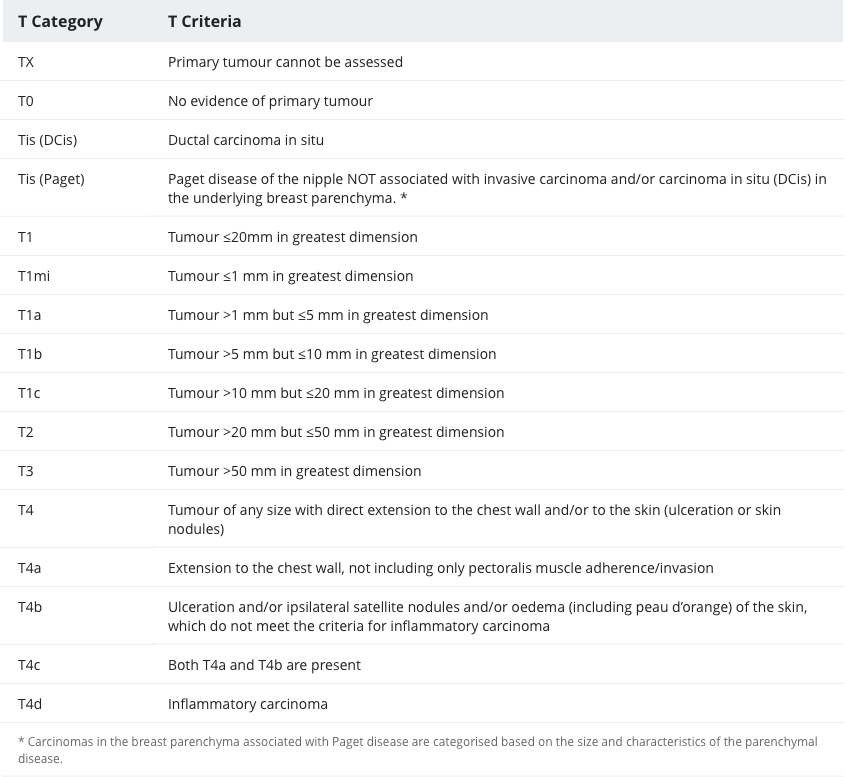

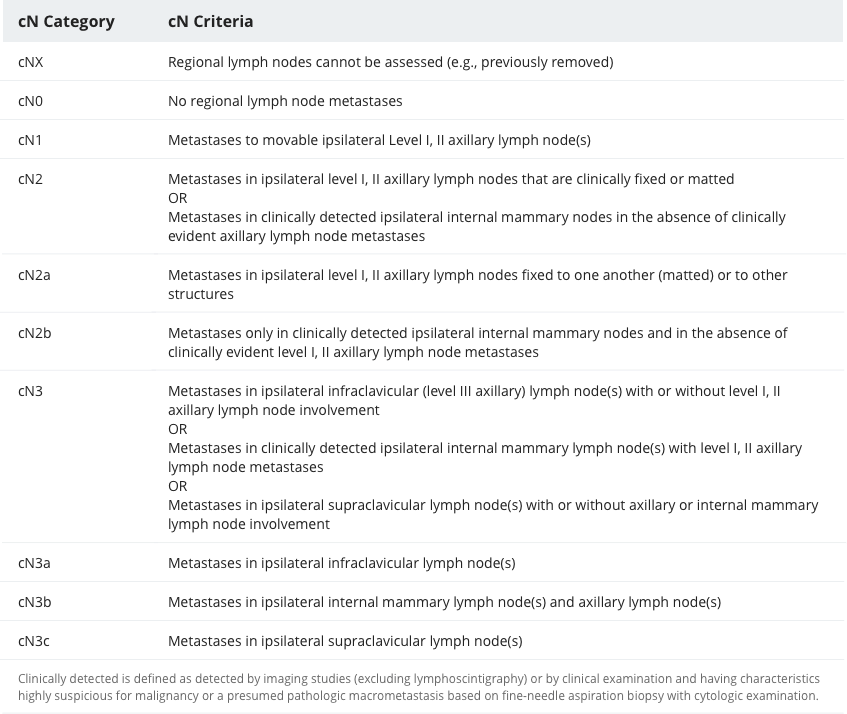

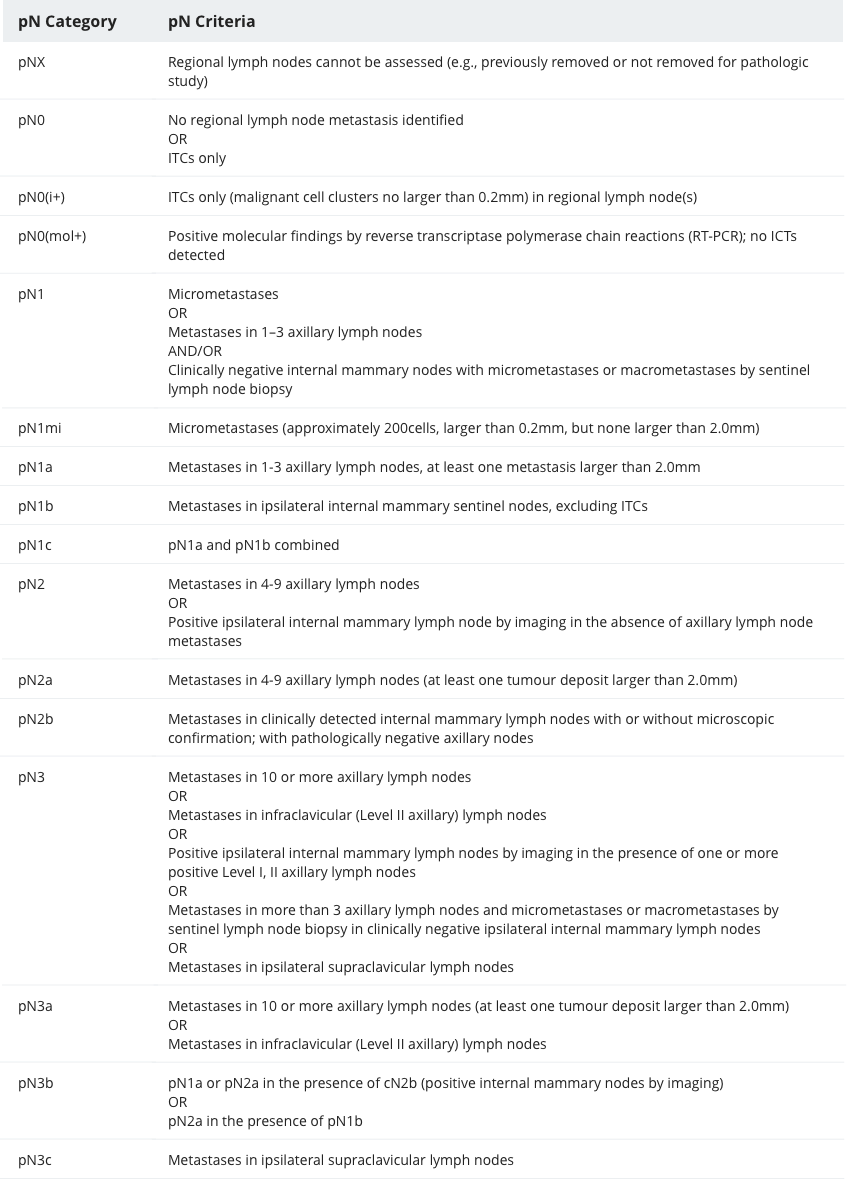

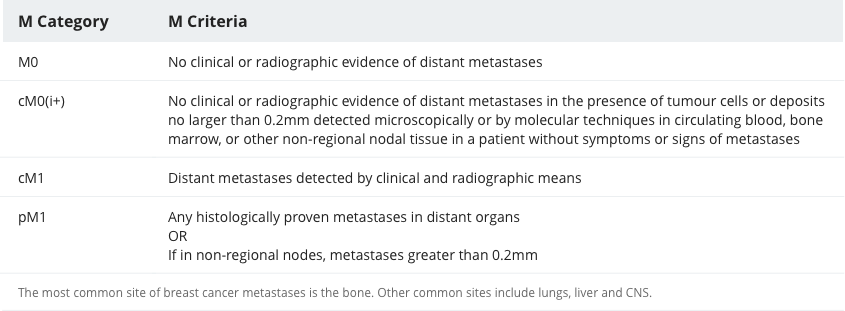

The complete criteria for categorisation of T, N and M, both for clinical (c) and pathological (p) staging can be found below.

Table 3. TNM Staging System for Breast Cancer based on the Cancer Staging System from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Genetics

Only 5 to 10% of all BC cases are hereditary. Many known genes are associated to a higher risk of BC, including BRCA1 and BRCA2, TP53, PTEN, CHEK2 and PALB2.

BRCA1 and BRCA2

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are genes responsible for

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

suppression that, when mutated, lead to an increased risk for both breast and ovarian cancers. They are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and present different levels of penetrance. Some populations, like the Ashkenazi Jewish, present a higher frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

BRCA1 is located on the chromosome 17, and its mutation is involved in around 45% of hereditary BCs and 80% of hereditary ovarian cancers. The lifetime risk of a woman who has a BRCA1 mutation corresponds to approximately 85% for developing BC and 40% for developing ovarian cancer. Due to the autosomal dominant pattern, each child has a 50% chance of acquiring the mutation. BCs associated to BRCA1 usually present in an earlier age, with a higher risk of bilateral involvement. Mutations in BRCA1 also increase the risk for malignant diseases in men who carry the trait, mainly for breast, prostate and pancreatic cancers.

BRCA2 is located on the chromosome 13. Carriers of BRCA2 mutations present a lifetime risk of roughly 85% for BC, and close to 20% for ovarian cancer. Similarly to BRCA1, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation. BRCA2-associated BC also manifest themselves in an early age, and bilateral disease is more frequent than in sporadic cases. These cancers, however, are more frequently well differentiated and hormone-dependent, which contrasts with BRCA1-associated

tumours.

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

Mutations in BRCA2 are associated with other malignant diseases besides BC and ovarian cancer, mainly colon, pancreatic and gastric cancers, but also melanoma. Men with BRCA2 mutations have a lifetime risk of developing BC that corresponds to 8%.

CHEK2

The checkpoint kinase 2 (CHEK2) gene is an important player in

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA)

The nucleic acid molecule that contains all the genetic information regarding the development and functioning of all living organisms is known as deoxyribonucleic acid.

damage repair. Mutations on CHEK2 showed to enhance the risk of BC by 2 to 3-fold. This alteration seems to be more common in white women originating from Northern or Eastern Europe and is associated with 0.5 to 3% of all familial BC cases. The lifetime risk of carriers of developing BC revolves around 37%. Other malignant

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

are also associated to CHEK2 mutations, especially colorectal cancer (CRC), gastric, prostate, and thyroid cancers. Male carriers are also at greater risk of developing BC.

PALB2

Primarily related to a special type of anaemia (Fanconi’s anaemia), mutations in the PALB2 gene also show to increase the risk of BC in a similar magnitude to BRCA2 mutations. The lifetime risk for women who carry the trait corresponds to 33 to 58%. Other malignancies have also been associated to the PALB2 mutation, such as pancreatic cancer, prostate and BCs for men, and ovarian cancer for women. The causality, however, is yet to be determined.

TP53 gene

The TP53 gene codes the production of the p53

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

,

which functions as a

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

suppressor, coordinating cell division by blocking the uncontrolled proliferation. Due to its importance in controlling cell division, p53 is frequently referred to as the “guardian of the

genome

Genome

A collection of DNA which is capable of developing and maintaining an entire organism.

”.

When mutated, the TP53 produces the Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, an autosomal dominant syndrome associated to the predisposition to several types of malignant diseases, especially BC, bone cancers, CNS

tumours,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

and soft tissue sarcomas, typically in children, adolescents and young adults.

TP53 mutations are estimated to cause less than 1% of all hereditary BCs in the world. Carriers have a risk of around 30% of developing any type of cancer by the age of 15 years, 50% by 30 years of age, and 90% by the age of 70 years.

PTEN

The PTEN gene codes the production of an enzyme that acts as a

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

suppressor, controlling the cell proliferation. Mutations in the PTEN gene cause an autosomal dominant syndrome called Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is characterised by the presence of multiple cutaneous and mucosal hamartomas and an increased risk for the development of some malignant

tumours,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

especially breast, thyroid and endometrial cancers. BC is diagnosed in approximately 30% of women who carry PTEN mutations.

Treatment

BC treatment is based on five different modalities: surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy and endocrine therapy. These modalities are applied in various combinations, depending on the size of the

tumour,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

the stage of the disease at diagnosis and the molecular expression of different receptors.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment modality for BC. Two different types of breast surgery can be applied, Breast Conserving Surgery (BCS) and Mastectomy. The choice between the two options depends on the size of the

tumour,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

the volume of the breast and the number of

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

in the breast: single

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

that measure up to 2 to 2.5cm or take up to 20 to 30% of the breast are generally treated with BCS; bigger

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

or multiple

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

have to be managed with mastectomy. It is crucial to highlight, nonetheless, that a BCS will invariably be followed by breast radiation therapy, in order to reduce the risk of local recurrence.

Regarding the axillary surgery, it will always be performed in cases of invasive carcinoma. When axillary lymph node involvement is diagnosed prior to the surgical procedure (through FNA or core biopsy), an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is performed. The sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNLB) is executed in all other cases and can be followed by ALND depending on the status of the intraoperatory axillary assessment.

DCis is treated either with BCS or mastectomy, depending on the size and the number of foci. In case of BCS, radiation therapy is mandatory. Axillary surgery is not necessary in cases of DCis, since these cancer cells are not capable of invading lymphatic structures.

After mastectomy, reconstructive surgery can be performed either as immediate reconstruction (at the time of the mastectomy) or as delayed reconstruction. It can be done using implants, tissue expanders or muscular flaps.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs with cytotoxic effect, to either kill cancer cells or stop their division. Since these drugs are not selective to cancer cells, normal cells of the body can also be affected by the treatment.

The need for chemotherapy is determined by the stage of the disease and the molecular characteristics of the

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

It can be administered either before the surgery (neoadjuvant setting) or after the surgery (adjuvant setting).

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is generally used in patients with locally advanced disease (stages II and III) aiming at

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

reduction, which could allow a less extensive surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can promote a reduction of the

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

size equivalent to 50 to 80%. Similarly to the adjuvant chemotherapy, the neoadjuvant treatment can eradicate undetectable disseminated

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

cells.

The regimens prescribed in the neoadjuvant context are the same as the ones used in adjuvancy. The most commonly applied are the anthracycline-taxane based. In HER2-positive BC, trastuzumab, a targeted therapy, should be associated in the neoadjuvant context.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is administered after the surgical treatment. In early stage invasive BC it is recommended in cases that present a greater likelihood of having systemic recurrence. Traditional indications comprise

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

larger than 1cm, node-positive cancers, and

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

with a high-risk biological profile. High risk features include HER2-positive cancers, negative ER/PR, high histologic grade, and blood vessel or lymph vessel invasion.

Anthracycline-taxane based regimens are the most commonly prescribed in the adjuvant setting, proven to reduce BC mortality by roughly 30%. Another common option consists in the association of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil.

In HER2-positive cases, the classical chemotherapy regimens should be combined with the use of trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to the HER2

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

.

This treatment promotes the reduction of the risk of recurrence in 50%.

In metastatic BC, chemotherapy plays an important role. The drugs to be used will depend on the treatments previously received. In HER2-positive metastatic BC the combination of taxane with trastuzumab and pertuzumab figures as the first-line treatment.

Radiation Therapy

Radiotherapy is also frequently used as an adjuvant therapy modality. The aim of this method is to reduce the risk of local recurrence. As a general rule, radiation therapy has to be performed after a breast conserving surgery, so that the risk of local recurrence is similar to the one reached with a mastectomy. After mastectomies, radiotherapy is used in cases of higher risk of local recurrence - positive axillary lymph nodes (especially more than four positive lymph nodes),

tumours

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

measuring over 5cm, and positive margins after surgery, when a surgical removal is not feasible.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy uses substances that attack only cancer cells. As opposed to chemotherapy, this type of treatment does not affect normal cells. Targeted therapies for BC include monoclonal antibodies, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors.

Monoclonal antibodies are very well-known in the treatment of HER2-positive BC and include trastuzumab and pertuzumab. They can be used both in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, as well as in the management of metastatic BC.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors intercept the mTOR

protein

Protein

Large biomolecules, which consist of one or more long chains of amino acid residues. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms including transporting molecules, providing cellular structure and catalysising processes such as DNA replication.

, preventing neovascularisation and

tumour

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

growth. Everolimus is an example that is used for advanced hormone-dependent BC.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors block signals that promote the growth of cancer cells. Lapatinib and Neratinib are examples of tyrosine kinase inhibitors used in HER2-positive BC.

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors halt proteins that promote cancer cells to grow. Examples include palbociclib, ribociclib and abemaciclib, used mostly in metastatic BC.

Endocrine Therapy

Endocrine therapy, also called hormone therapy, is recommended in all cases of hormone-dependent BCs.

In premenopausal women, the use of tamoxifen for 5 years is the traditional recommendation. Ovarian suppression with LHRH analogues could be considered for patients with higher risk of systemic recurrence – factors such as young age, high-grade

tumours,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

lymph node involvement are associated to a higher risk of recurrence. Tamoxifen is an ER modulator that acts as an antagonistic on the breast cells. It was found that the use of tamoxifen for 5 years reduces the risk of recurrence by 40% and the risk of death by 30% in cases of ER/PR-positive

tumours.

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

For postmenopausal patients, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) for 5 years are preferred, nonetheless tamoxifen can also be considered. The aromatase is an enzyme responsible for the conversion of androstenedione into oestrone, which is the main mechanism responsible for oestrogen production after menopause. The enzyme is found in the adipose tissue, and also in breast tissue and BC cells. AIs are able to block this conversion, reducing the production of oestrogen. Since in premenopausal women the oestrogen is produced in the ovaries by reactions that do not involve aromatase, isolated AIs are not appropriate for endocrine therapy in these patients.

Endocrine therapy is the preferred treatment alternative of hormone-dependent metastatic BC. Options include tamoxifen, AIs and fulvestrant, a selective oestrogen receptor degrader. In premenopausal patients, the association of ovarian suppression should also be considered.

Epidemiology

BC is the most common malignant disease in women worldwide after non-melanoma skin neoplasms. It is responsible for around 30% of all new cancer cases in women and 14% of all cancer deaths in this part of the population. It is estimated that women present a BC risk of 12% during their lifetime. Although it can occur in the majority of age groups, BC becomes increasingly more common after the age of 40. Most cases are diagnosed in women older than 50 years of age.

The burden of BC varies greatly between different regions of the world. Overall, the burden of BC tends to be higher in the densely industrialised countries of Europe and North America, mainly due to the aging of the population, dietary habits and reproductive aspects. In contrast, BC is less frequent in poorly industrialised and urbanised countries of Asia and Africa.

In order to compare incidence and mortality rates between countries with different structures, the age-standardised rate (ASR) can be applied. The ASR is a measure of the rate of a disease or condition that a population would have if it had a standard age structure. It is useful to compare populations that have different structures and it is expressed per 100,000 people. While in more resourced countries the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) is 73.4 per 100,000 people, the same rate corresponds to 31.3 per 100,000 people in less resourced regions. Comparing the age-standardised mortality rates (ASMR), on the other hand, we find very similar values between these two different groups: 14.9 per 100,000 in more resourced countries, and 11.5 per 100,000 in less resourced ones.

Despite these contrasts, nonetheless, incidence rates are presenting progressive increase in the majority of regions of the world.

Survival rates for BC also show variation between different countries, with the tendency to be lower in low- and middle-income countries and greater in high-income countries. In Brazil, an upper-middle-income country, the 5-year overall survival rate corresponds to 72.1% in recent study.

In the US, a high-income country, the same rate reaches 89.7%. Survival rates are highly dependent of the stage of the disease at diagnosis, with 5-year overall survival rates higher than 95% for localized disease and lower than 30% for metastatic disease.

Risk Factors

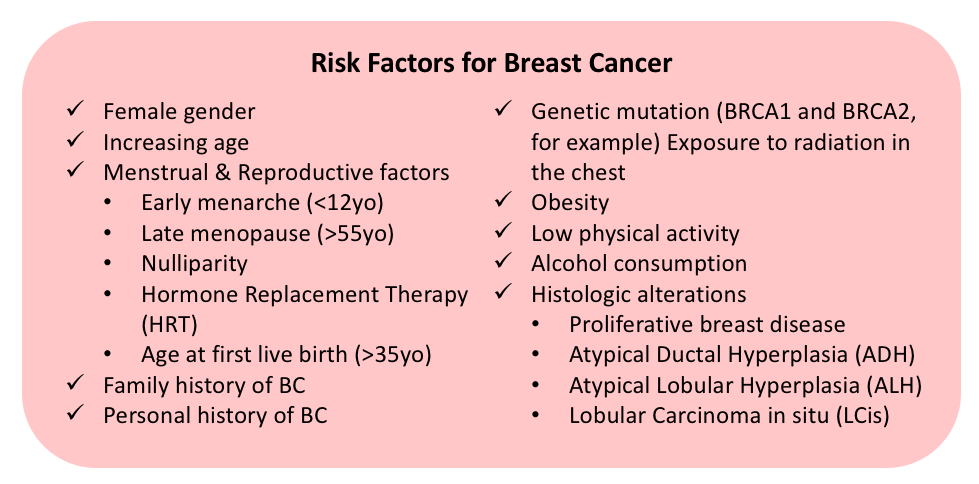

Known risk factors for BC are many and include female gender, increasing age, increased exposure to oestrogen, family history and others, as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 2. Risk factors for Breast Cancer (adapted from Sabiston Textbook of Surgery).

Age is one of the most important risk factors for BC. The mean age of diagnosis of BC in women is around 60 years, and the risk of BC increases throughout the life of a woman. The disease is uncommon before the age of 20, nonetheless its incidence increases progressively after the age of 40. From 1 case in every 69 women between 40 and 49 years of age, the incidence of BC reaches 1 in 29 between 60 and 69 years of age and 1 in 8 women aged 80 years.

Gender is also a critical risk factor for BC, since most cases of the disease occur in women. Although it can appear in men, male BC is responsible for 1% of the cases only.

Family history figures as another relevant risk factor for BC. Diagnosis of BC in a first-degree relative increases the risk of a woman in two to three-fold, and this risk rises further when the relative had the diagnosis before menopause or bilateral BC. History of BC in two or more first-degree relatives is associated to an even higher risk. More than 75% of women diagnosed with BC, however, have no family history of the disease.

Several reproductive factors are related to an increased risk for BC. Nulliparity and late first live birth (first full-term pregnancy after the age of 35) can increment the risk in 1.5-fold, in comparison to multiparous women. Early menarche (before 12 years of age) and late menopause (after 55 years of age) are additional factors associated to a higher risk of BC. The elevated risk in these cases is related to the heightened exposure to oestrogen during life. Obesity is another factor that increases the risk of BC through the same mechanism. Since after menopause the majority of the oestrogen available is obtained by the conversion of androstenedione to oestrone in the adipose tissue, obesity also leads to an elevated oestrogen exposure. In contrast, factors that reduce the time of oestrogen exposure, such as longer lactation period and physical activity, have a protective effect.

Personal history of BC increases the risk of a second cancer in the contralateral breast. The magnitude of this risk depends of factors like the age at diagnosis and the molecular type of the

tumour,

Tumour

The abnormal growth of cells that causes swelling or lesion is known as tumour. A tumour can be malignant or benign. One should not confuse cancer with tumour as cancer means malignant.

but it is estimated to be between 1 and 2% per year.

Despite some studies suggesting that oral contraceptives are associated to an increased risk of BC, there is much controversy regarding the subject, therefore no recommendations are available at this point. Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) after menopause, on the other hand, has been shown to increment the risk of BC in a sensible way, especially when progesterone and oestrogen are used together.

A slight risk increase is observed with alcohol consumption. Some studies suggest that the risk of developing BC is incremented proportionally to the amount of alcohol consumed, however this is still controversial.

Only 5 to 10% of cases of BC in women are attributed to genetic factors. This proportion, nonetheless, can reach around 25% of cases when we consider exclusively women younger than 30 years.

Previous radiation exposure can elevate the risk of BC in an accentuated way. Women who went through radiation therapy in the chest at as children, adolescents and young adults, as a treatment for lymphomas for example, present a risk of BC than is 75 times higher than the general population.

Some histologic alterations are present on the list of risk factors for BC. Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) are two types of proliferative breast disease with associated atypia. These two conditions lead to an increase in the BC risk equivalent to four to five-fold the risk of the general population, which corresponds to an annual risk of 0.5 to 1% per year. Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCis) is yet another condition associated to a higher risk for BC. In women with LCis, the risk of developing BC is said to be around 1% per year.

Additional Resources

Strength for Life

Strength for Life a personal training studio which has had several clients who have had breast cancer, providing a safe and effective exercise program for them. Below are links to two of their blog posts:

Is Exercise Safe For Breast Cancer Survivors?

https://www.strengthforlife.us/post/is-exercise-safe-for-breast-cancer-survivors

Why I Exercise After Breast Cancer

https://www.strengthforlife.us/post/why-i-exercise-after-breast-cancer-by-marianne-dietrick-gallagher

Shades of Pink Foundation California

The mission of the Shades of Pink Foundation California is to provide temporary monetary assistance to women who are experiencing financial distress as a result of a breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Serving California women.

https://shadesofpinkfoundationca.org/

References

- "American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). AJCC Cancer Staging system. 2017. Available from: https://cancerstaging.org/Pages/default.aspx"

- "Cameron JL, Cameron AM. The Breast. Current Surgical Therapy. 10th ed. London; Elsevier Saunders; 2011."

- "Cancer Research UK [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/"

- "Cancer Research UK [Internet]. Risk factors for breast cancer. 2017. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/breast-cancer/risks-causes/risk-factors"

- "Elmore JG, Armstrong K, Lehman CD, Fletcher SW. Screening for Breast Cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;293(10):1245-56."

- "Fentiman IS, D’Arrigo C. Pathogenesis of Breast Carcinoma. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58(1);35-40."

- "Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Global Burden. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524–48."

- "Giuliano AE. Breast. Current Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006."

- "Hunt KK, Green MC, Buchholz TA. Breast. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. London; Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012"

- "Hunt KK, Robertson JFR, Bland KI. The Breast. Schwartz Principles of Surgery. 10th ed. vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2015."

- "International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [Internet]. The Global Cancer Observatory. 2018. Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr/"

- "National Cancer Institute (NCI) [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov"

- "National Cancer Institute (NCI) [Internet]. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result Program (SEER). 2017. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov"

- "National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [Internet]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast Cancer Version 1.2018. 2018. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf"

- "National Institute of Health (NIH) [Internet]. Genetics Home Reference. 2018. Available from: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov"

- "Romero N, Castro E. Inherited mutations in DNA repair genes and cancer risk. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41;251-264."

- "Sankaranarayanan R, Boffetta P. Research on cancer prevention, detection and management in low- and medium-income countries. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(10):1935–43."

- "Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rutgers E, Zackrisson S, Cardoso F. Primary Breast Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(suppl 5):8-30."

- "Shah R, Rosso K, Nathanson SD. Pathogenesis, Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(3):283-298."

- "The Yorkshire Breast Cancer Group. Symptoms and signs of operable breast cancer. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1983;33:473-6."

- "World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. Cancer. 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/en/"

- "World Health Organization. WHO Position Paper on Mammography Screening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25642524."

- "D’Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA, et al. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA, American College of Radiology; 2013"